History of the University of Alabama

The

History of The University of Alabama begins with an act of

United States Congress in 1818 authorizing the newly formed

Alabama Territory to set aside a township for the establishment of a "seminary of learning."

Alabama was admitted to the

Union

on March 20, 1819 and a second township added to the land grant. The

seminary was established by the General Assembly on December 18, 1820

and named

The University of the State of Alabama.

The legislature appointed a Board of Trustees to handle the building

and opening of the campus, and its operation once complete. The Board

selected

Tuscaloosa, then capital of the Alabama, as the site of the university in 1827, and opened its doors to students on April 18, 1831.

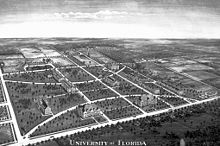

The school in writing: 1820–1831

The original land grant included the entire area within the

Tuscaloosa

city limits stretching south of what is now University Boulevard to the

AGS Railroad and west to Queen City Avenue. The land had been owned by

William Marr, whose name is commemorated today in Marrs Spring and the

literary Marrs Field Journal. A prominent

architect, Captain William Nichols, was commissioned to design the campus.

Most of the material for the early buildings came from university land.

Slaves quarried

sandstone near the

Black Warrior River, burned and made

bricks on the spot, and cut

lumber from the university's own

timber tract. An extensive

vineyard was situated in the area of Denny Field and Barnwell Hall.

The frontier school: 1831–1860

The Board of Trustee selected the Reverend Alva A. Woods to be the first president of the university. Educated at

Phillips Andover,

Harvard College and in Europe. Woods hoped to turn the university into a Harvard-style seminary.

Admission standards were set high. Simply to enter the university, one had to demonstrate the ability to read

Classical Greek and

Latin

at an intermediate level, with advanced study in those languages to

begin immediately. But Alabama, a frontier state a sizable amount of

whose territory was still under the control of various Native American

tribes, was decades away from possessing the infrastructure necessary to

provide adequate education (public or even private) to meet such high

standards.

The university was consequently forced to admit many students who

were not adequately prepared for university education. For the duration

of the Antebellum period, the university would graduate only a fraction

of those young men who entered. Of the 105 student who enrolled in 1835,

only eight graduated.

Within a month of the opening of the university, social societies

emerged. Unlike the social fraternities that would emerge in the next

decade, these clubs were academic debate societies by nature. The

Erosophic Society was founded in May 1831, while the Philomathic Society

came out eight months later.

For $80 a year, students received room and board at the Hotel, now

known as the Gorgas House. Washington Hall and Jefferson Hall, called

the "colleges," stood three stories high. Each contained twelve

apartments, which in turn contained two bedrooms and a sitting room.

Forty-eight students resided in each

dormitory. Madison and Franklin Halls were built later. Following the

American Civil War,

the remains of Madison and Franklin Halls were made into memorial

mounds. Madison Mound was removed during the 1920s, but Franklin Mound

is still used for Honors Day ceremonies. Additionally, an archaeological

excavation, conducted in 2007, examined the remains of Washington and

Jefferson Halls foundations.

At the center of the campus, where the Gorgas Library is now

situated, stood the "grande dame" of the university, the Rotunda. In the

1894 yearbook,

Corolla, the building is described as "a circular

edifice of three stories, seventy feet in diameter and seventy feet in

height, and surrounded by a lofty peristyle of the

Ionic order

of architecture. The principal story was used for chapel service and

academic recitations. This department was long celebrated as being the

finest auditorium in the State. In the second story was the circular

gallery, supported by carved columns of the

Corinthian order.

The third story contained the library and the collections in natural

history." The Rotunda was destroyed by fire and was never rebuilt.

Following an

excavation in 1985, the Rotunda's remains were cushioned in sand and covered with concrete to mark where the building had once stood.

Greek life began at the university in 1847 when two young Mobilians visiting from

Yale installed a chapter of

Delta Kappa Epsilon.

When DKE members began holding secret meetings in the old state capitol

building that year, the administration strongly voiced its disapproval.

Over the next decade, three other fraternities appeared at Alabama:

Phi Gamma Delta in 1855,

Sigma Alpha Epsilon in 1856, and

Kappa Sigma

in 1867. Anti-fraternity laws were imposed in that year, but were

lifted in 1890s. Eager to have a social organization of their own, women

at the university founded the Zeta Chapter of

Kappa Delta sorority in 1903.

Alpha Gamma Delta and

Delta Delta Delta soon followed.

The military school: 1860–1902

In the 1850s, the school's president,

Landon Garland,

began lobbying the Legislature to transform the university into a

military school. In 1860, in the wake a violent brawl which resulted in

the death of student as well as the impending war, the legislature

authorized Garland to make the transformation beginning in the Fall of

1860. As a result of this transformation, during the

Civil War, the school trained troops for the

Confederacy.

Because of this role,

Union

troops burned down the campus in April 1865. Only seven buildings

survived the burning, one of which was the President's Mansion - and its

outbuildings. Frances Louisa Garland, wife of President Landon C.

Garland, saved the home from destruction by the Union soldiers. When she

saw flames in the direction of the campus, she ran from the Bryce home

where the family had taken refuge and demanded the soldiers put out the

fire in the parlor. The university reopened in 1871 and shortly after,

the military structure was dropped. The other principal buildings today,

have new uses. Gorgas House (

http://gorgashouse.ua.edu/),

at different times the dining hall, faculty residence, and campus

hotel, now serves as a museum. The Roundhouse, then a sentry box for

cadets, later a place for records storage, is a campus historical

landmark. The Observatory, now Maxwell Hall, is home to the

Computer-Based Honors Program.

In 1880, the

United States Congress

granted the university 40,000 acres (160 km²) of coal land as partial

compensation for the $250,000 in war damages. Some of the money went

toward the building of Manly and Clark Halls. In 1887, Clark became the

home of the library, whose 7,000 volumes had been destroyed. It was not

until 1900 that private donations, including the donation of 1,000

volumes collected by John Leslie Hibbard's father, restored the library

to 20,000 books. Garland Hall, which housed the

geology museum and lecture rooms, completed what became known as Woods Quad. Tuomey and Barnard Halls were also built before 1900.

The

medical school and pharmacy school was in

Mobile at the time.

[1]

The growing university: 1902–1941

Clark Hall was rebuilt after the Civil War

The university was officially opened to women in 1892 after much lobbying by

Julia Tutwiler

to the Board of Trustees. In 1895, it was advertised that "young women

of good character, who have attained the age of eighteen, may be

admitted to the university, provided they are prepared to take up

subjects of study not lower than those of the Sophomore class. They must

reside in private families; but rooms for study during the study-hours

of the day are provided at The University."

Although the university attempted to look forward to the 20th

century, some elements of the past remained. Four tombstones marked the

graves of Professor Horace S. Pratt and his family in a tiny cemetery

beside the

biology

building. In celebration of the university's seventy-fifth anniversary

in 1906, President Hill Ferguson and Robert Jemison launched a

fund-raising campaign with the slogan, "A quarter million dollar

improvement fund." The $5,000 which the campaign secured from the state

legislature in 1909 went toward the building of Smith and Morgan Halls.

Constructed of yellow

Missouri brick with

Indiana limestone trim, the buildings reflected the

Beaux-Arts Greek Revival style of architecture that was popular at the turn of the 20th century.